Pocket water fly fishing tactics

Jan. 27th, 2022

Pocket water fly fishing is a lost art, in my opinion. But, it’s not because pocket water is rare. On the contrary, pocket water can be found in most rivers and streams across the United States.

In my experience, of all the usual sections that comprise rivers and streams, including runs, riffles, and pools, fly anglers are least likely to be found in the pocket water sections. Maybe the water looks unfishable to them, or they’d prefer a less physically demanding day of fishing, but either way, I’ve never come across another fly angler in pocket water. Ever.

So, if you’d like to learn pocket water fly fishing techniques, you’ve come to the right place. I’ve spent countless serene hours catching trout in pocket water in small rivers, large rivers, and streams.

In the below article I’ll include several pictures to help you identify pocket water, as well as fishing tactics, timing, productive fly patterns, and the gear I recommend.

In the below picture, I’m fly fishing in some productive pocket water. I’ve added white arrows to show where I caught trout in this section. The top arrow was a rainbow, and the bottom arrow was a brown trout.

What is pocket water?

Pocket water is defined as a section of a river or stream where boulders and large rocks protrude above the surface. The turbulent and chaotic currents within pocket water are disrupted both above and behind the boulders and large rocks, creating “pockets” of calmer water.

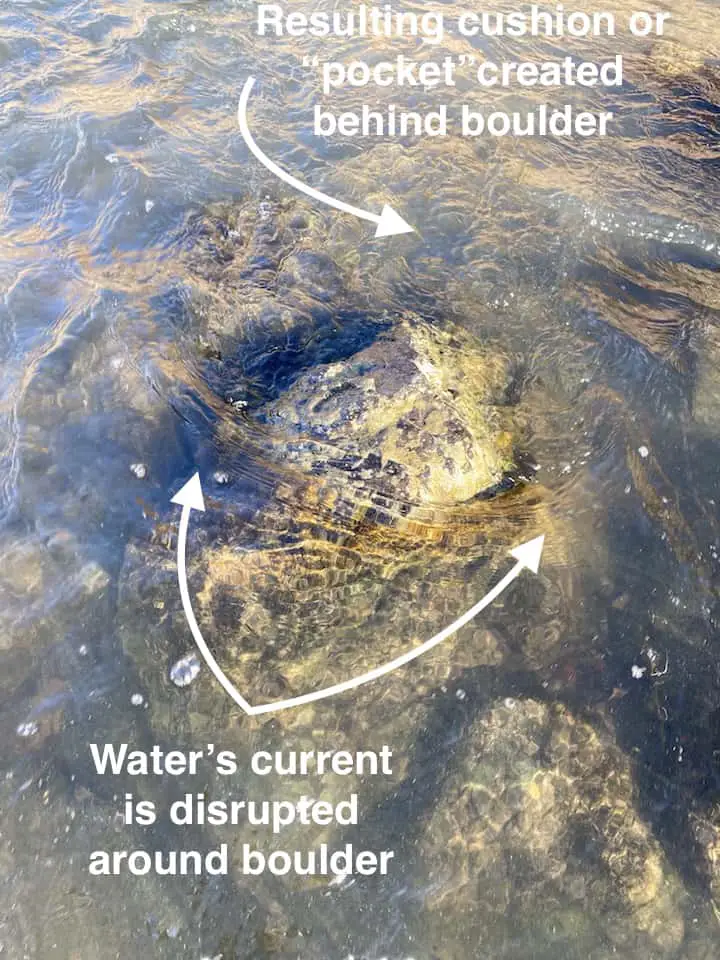

Here’s a picture I took with some added notes to help you visualize what I mean.

Remember, a “pocket” is created both in front of, and behind, the boulder. Fortunately for you, these pockets of slower water often hold trout that are waiting for drifting insects to consume. Fish are drawn to pocket water for a couple reasons.

Firstly, the water is highly oxygenated by the turbulence.

Secondly, since pocket water is usually shallower, the sun can penetrate to the bottom providing for plenty of algae growth, which attracts insects.

Sight-fishing is a little more challenging in pocket water because of the chaotic surface currents, but in the sections of slower water you’ll often see trout holding together, often below areas where water falls into a lower section.

Here I am about to fly fish through some nice boulder-strewn pocket water that holds primarily small to medium brown trout. Notice the boulders and rocks, the active current, and the shallow water.

Where to Find Pocket Water

Almost every river and stream in America contains sections of pocket water, peppered in with runs, riffles, and pools. Even small creeks and brooks (yes, there’s a difference) often have plenty of pocket water.

In fact, my absolute favorite type of pocket water fly fishing is in remote mountain rivers and streams. The tranquil atmosphere, nature active all around you, the soft sound of flowing water, hungry trout ready to strike, and the fact that I never come across other fly anglers–it recharges my soul.

Here’s a picture of a juvenile rainbow trout I caught while fly fishing pocket water in the Sierras of California. Even small fish like this are a ton of fun to catch when you’re up close and personal. Don’t forget to check out my article all about fly fishing for rainbow trout.

It’s difficult to describe where exactly you’ll find pocket water. It’s far from rocket science. Some rivers I fish are almost entirely comprised of pocket water. Literally, for miles.

Be on the lookout for shallower sections with active current, littered with many boulders and/or large rocks protruding from the surface. Additionally, the downward slope of the river is usually steeper in these areas.

Here’s a video I took of some gorgeous pocket water flowing into a pool in the mountains. I fished this river for seven hours and didn’t see another person.

Fly Fishing Tactics for Pocket Water

One of the beautiful things about pocket water is that you’re close to the action. By that I mean, you’re never far from where the fish takes your fly. You watch the entire process unfold.

There are a couple reasons for this.

Firstly, the surface of the water is choppy, and so you can get closer to fish without being detected. This is because it’s much more difficult to see the outside world (from underwater) when the surface isn’t calm.

Secondly, you just plain can’t make long casts in pocket water–the chaos of the current will wreak havoc with your line and leader. There’s just too much contrasting current for lots of line on the water. In other words, it’ll create near-instant drag. You need to make short casts to specific spots.

The first thing to remember when you’re fly fishing in pocket water is that the swift and alternating currents mean preventing drag is challenging. Mending is tougher too, when you’re surrounded by obstructions. You need to maintain focus.

Avoid casting into fast water with turbulence–fish aren’t holding there. It’s too much work for them.

You’ll want to cast to the following spots when you’re fishing in pocket water.

Fishing Around Boulders

If you recall, boulders (and large rocks) cushion the current of the water, creating “pockets” of calmer water in front of, and behind, the boulder itself. As a result, trout will hold in front of, and behind, these boulders.

The reason trout hold here is because they don’t have to expend much energy to maintain their position. Minimizing caloric output is critical for fish to survive and grow. They must always strike a delicate balance between calories consumed, and calories burned. If they burn more calories than they consume, it’s lights out.

So, trout hold in the relatively calm water in front of (and behind) boulders, where they can wait for the faster current to bring insects near them. Think of the faster current as a conveyor belt of insects. Trout let the current bring them food–it’s very calorie efficient.

Trout will dart up, down, and side-to-side picking-off isects that drift by them.

There are several methods for casting near boulders.

Firstly, you can cast several feet upstream of the boulder in an attempt to entice trout holding in front of the rock. If there are no takers, I let the current carry my fly right around behind the boulder. Obviously, keep your fly on your side of the boulder at all times–don’t allow your fly to go around the opposite side of the boulder from where you’re standing or you’ll just get snagged.

Secondly, you can cast alongside the boulder–within two feet or so of the rock. Trout can, and will, dart out into faster current if they see something worth their while.

Thirdly, cast behind boulders–land your fly as tight as possible to the rock. This is my go-to method and will be for you too, in most situations.

This method holds true regardless of the type of fly pattern you’re using–dry fly, nymph, streamer, dry dropper, etc.

You can stand above, in-line with, or below the boulder–it just depends on your preferred method of delivering a fly, and the physical topography around you. Sometimes you’ll be forced to delivery your fly from a particular position. It’s all part of the fun.

fishing Short runs

These are short, narrow runs–sometimes just a few feet in length. You’ll find these peppered throughout most types of pocket water.

If you don’t remember anything else I say, remember this: don’t ever underestimate short runs. They’re gold mines, and the fishing is easy. I’m all for a challenge, but sometimes easy is nice.

Short runs hold fish.

The picture below was taken from the same spot as the video above. I’ve added a white arrow to show you where I caught several rainbow trout. It’s a short, shallow channel within the pocket water system.

Incidentally, the slippery-looking rock formation on the left side of the picture is where I took my hardest fall ever–while fly fishing anyway.

In the short run above, I stood below it and cast up to the top and let my dry fly drift down towards me. I didnt want to risk spooking the trout by standing on the side, or walking up past the run to delivery my fly from above. You can see the water was relatively placid, so they might’ve spotted me.

Casts are free. Experiment.

fishing below Waterfalls

When I see a waterfall, I’m always confident fish are holding below it. Even 6-inch waterfalls. The water is hyper oxygenated, the bubbles provide visual cover, and it carries with it bugs from above.

In the below picture, I absolutely knew fish were holding in that section below the waterfall. I’d never cast a fly into this river, but I knew.

Sure enough, within three or four casts, a feisty rainbow took my fly and I landed it a few seconds later. I’ve added a white arrow to show you exactly where I saw the trout rise and take my elk hair caddis pattern.

Dapping method

Dapping is a method where you only allow your leader, tippet, and fly on the water, but not your actual fly line. I refer to it as a type of “high sticking,” even if you’re using dry flies instead of nymphs. It’s not my favorite method, but sometimes conditions call for it.

For instance, there may be a narrow section where you can’t cast at all, or you’re concealing yourself behind a boulder and targeting fish just a few feet in front of you, or maybe a cast is just plain unwarranted.

Either way, dapping is something you’ll do often when you’re fly fishing pocket water, especially on smaller streams and rivers.

In simple terms, you’re picking your fly off the water’s surface by lifting your fly rod, and then you rotate back to where you started (usually upstream) and begin drifting your fly again. All the while you only have 8-12 feet of monofilament line out of your guides.

Dapping can be really useful when currents are an issue, because you’re easily able to eliminate drag due to having so little line on the water.

There is one negative aspect of this dapping, namely that your rod is often swinging over the fish, which can spook them.

When I’m dapping, I prefer to use a dry fly. I like the interaction at the surface when a trout strikes.

Here’s a picture I took of a spot where I caught several trout using the dapping method. The white arrow points to the exact spot where most of the action took place.

Streamside vegetation

To me, there’s just something so undeniably alluring about overhanging streamside vegetation, be it trees, bushes, or plants. The mere sight will excite me.

Trout love to hunker down under overhanging shoreline vegetation. In other words, vegetation that reaches out over part of the water. It provides fish with cover (and thus security), and insects that fall from the leaves and branches. Sometimes times these spots hold big fish.

These types of spots are commonly found along waterways, but they always leave you with an impactful decision to make.

Pop quiz hotshot. An accurate cast coupled with a drag-free drift will likely yield you a trout, but a misplaced cast will leave you hung-up in the bushes resulting in frustration and precious time lost. What do you do?

I always cast. Always.

If you want to be “safe,” you could carefully wade up above the streamside bushes or trees without spooking the fish, let some line out, and allow your fly to drift downstream under the overhang. Not my cup of tea, but to each his own.

I cast, and I’m usually glad I did.

Every approach is different, and I really enjoy planning my cast in these situations. I’m not going to get into the various types of casts I use–everyone has their own style.

Once you make an accurate cast, it’s hugely gratifying. Then, you’re riveted and pulsing with anticipation as your fly drifts along the path you’ve chosen.

The only thing that makes the above scenario better is when a foamline is running underneath the overhanging vegetation. Pure serendipity.

the Boulder assist

Fly fishing in pocket water means you’re never far from boulders and large rocks. Once in a while, whether intentionally or unintentionally, your fly will land on a rock. Not snagged, just sitting there on a rock.

Give your fly a twitch and let it fall into the water, like a dislodged insect. Trout will often take notice and eat your fly.

Another tactic that can occasionally come in handy is letting our fly line sit on top of a rock as your fly drifts drag-free downstream.

Specifically, imagine you’re standing in pocket water and casting 45-degrees upstream, surrounded by swift currents. Sometimes the water grabs your fly line too quickly and creates near-immediate drag. If you can cast strategically so that your fly line falls onto a rock, it can hold your fly line in place, helping you achieve a drag-free presentation.

I don’t use this method all that often, but when I do it’s a godsent.

Here’s a short video of one of my favorite pocket water rivers, full of rainbows that chase dry flies.

The Best Pocket Water Fly Patterns

Trout in pocket water usually aren’t overly selective when it comes to flies. Once in a while you’ll hear some clown claim that pocket water trout are stupid, feeding with reckless abandon.

In actuality, the trout aren’t dumb–they’re simply opportunists.

Pocket water moves quickly, and hatches are more sparse than in other sections of the river, so fish must eat whenever they get the chance.

All that to say, here are the most productive flies I’ve used in pocket water, in no particular order.

Dry Flies for Pocket Water

I’ve spent countless hours fly fishing pocket water, and I’ve tried a lot of different dry fly patterns.

With that said, here are what I consider to be the best dry flies for pocket water, in no particular order: the blue winged olive (BWO), the humpy, the elk hair caddis, and the black ant. I usually start with a size 18 or 20. Rarely do I have to go smaller. In fact, bigger flies (sizes 14-16) can work really well too, even for smaller trout. (They’re greedy feeders.)

As I mentioned, you don’t need to wait for a hatch to successfully fish dry flies in pocket water. Also, you don’t need to agonize over the exact fly pattern matching the area’s insects. Pocket water fish are aggressive and usually aren’t overly selective.

If you see ants on or around shoreline vegetation (usually during the summer months), tie on an ant pattern. (Here’s another article I wrote on how to fly fish with ants.)

The elk hair caddis was tied to imitate a caddisfly, but it resembles so many different insects, including moths, mayflies, spiders, and various terrestrials. It’s a great, meaty fly for hungry trout.

Blue winged olives are a must-have fly for any fly angler, and pocket water fly fishing is no exception. Trust me, you want these in your fly box.

The humpy fly works particularly well in pocket water. It’s similar to the BWO, but it’s meatier with more coloration. Here’s a tip: I’ve had the most success using the humpy pattern with a red underside/belly.

Most of the time, I fish dry flies blindly–meaning there’s no hatch happening–with great success. Cast these flies in the spots I mentioned earlier, and you’ll bring plenty of fish to your net.

Most of the time, I fish dry flies blindly–meaning there’s no hatch happening–with great success. Cast these flies in the spots I mentioned earlier, and you’ll bring plenty of fish to your net.

Nymphs for Pocket Water

Nymphing pocket water can be hugely successful, especially if the trout aren’t taking food on the surface.

There are three nymphs I’ve had the most success using, and they are the pheasant tail, the hare’s ear, and the red midge (aka blood midge), in no particular order. I use the beadhead version of each, to get the fly down in the water column.

You can add some tungsten weight to your line (or another beadhead nymph) if you need to get deeper.

Just know that in shallow pocket water you’re going to get hung-up often. It’s just part of the game.

If I could only choose one nymph, it’d be the pheasant tail, hands-down.

Here’s a tip: try using dark beadheads (instead of brass) if your waters are heavily fished. I think trout can develop an aversion to shiny objects drifting through the water after being caught several times.

Streamers for Pocket Water

You might not think streamers would be very useful in pocket water, but they can work really well. Don’t count them out.

Two thoughts.

Firstly, I was recently on a river, doing quite well, casting a size 12 black beadhead woolly bugger. I came upon a long stretch of shallow (8-12 inch deep) pocket water. It wasn’t overly rocky, so I decided to work my way through it, even though it seemed like a low probability play.

I was casting almost directly upstream, stripping-back about 8-inches of line per second or so. Sure enough, I landed several nice trout.

Now, conventional wisdom would say that you don’t cast streamers upstream in pocket water. But I did, and it worked like a charm. That’s why I experiment a lot.

Conventional wisdom is often wrong.

Secondly, when you’re working your way through pocket water, you’ll almost inevitably come across a pool (or several). Pools are prime streamer territory.

In the below picture, you can see a pool I came across while fly fishing some pocket water in a beautiful forest. The pool looks almost sterile, but it was packed with rainbows–I caught around eight trout in this pool alone. Sure, they were small, but I got to watch them take my fly, which is riveting no matter the size of the fish.

Dry Droppers for Pocket Water

A dry dropper is a dry fly trailed by a nymph. The distance between the two flies is dependant upon the depth and speed of the water.

I generally use a dry dropper setup if the fish are primarily eating subsurface, but occasionally taking flies on the surface. It’s a version of having your cake and eating it too.

There’s nothing compolicated about it. The dry fly is acting as an “edible” indicator. The dry fly just needs to be buoyant enough to prevent the nymph from drowning it.

A setup I’ve had a lot of success with is a size 18 elk hair caddis trailed by a size 20 beadhead pheasant tail. But, there are an infinite number of combinations that’ll work for you. Experiment!

When to Fly Fish Pocket water

Pocket water can be fished year round, but unsurprisingly, there are prime times to hit the water if you want to increase your chances of hooking into some fish.

Spring pocket water

Springtime is a season of transition. The snow in the mountains is melting and the resulting frigid water feeds into rivers and streams.

This snowmelt causes river levels to rise due to the increase in water volume, which of course translates to faster water as well. So, you’ve got high, fast, cloudy, very cold water. Things can get a bit ugly.

The trout don’t appreciate fast water any more than you do because it makes them work harder (ie. burn more calories) to stay in position.

As a result, the trout hold closer to the shorelines, where the current is weaker.

Water can get so dirty during runoff that guides call it “chocolate milk.” But, the trout are still feeding. They don’t have the luxury of not eating. The high water does a good job of sweeping insects into the water.

Nymphs and streamers (think black woolly bugger) are usually the most productive pocket water flies during springtime in my experience.

Summer/Fall pocket water

This is prime time. The water is slower, warmer, and the levels have dropped (usually by June). No more chocolate milk, either–the water’s clear again.

Trout will be aggressively feeding both on the surface and below the surface, so you can use whatever flies you prefer.

If you’re going to choose a time, this is it. Nature is active, the sun is warm, and the fish are biting.

Another bit of well-intentioned conventional wisdom says that trout won’t come to the surface on sunny days because they don’t have eyelids. I think about this ridiculous and often parroted theory often. It’s just not true.

I’ve caught countless trout on dry flies during bright, sunny, cloudless days. Pocket water trout are even more willing to rise to a fly in bright sun than trout residing in riffles, runs, and pools.

It’d be more accurate to say that you’re more likely to get a trout to rise to your fly when the sun is blocked or partially obstructed. My whole point is, don’t ever let bright sun stop you from casting your flies.

If I could choose my fly fishing conditions, I’d want a cloudy day. But there’s no way I’m staying home just because it’s sunny.

I could go on and on about this subject, to the point that it would become stultifing, so I’ll stop.

Winter pocket water

Another advantage of the turbulence of pocket water is that often times it won’t freeze during wintertime temperatures.

I often see long stretches of slower water entirely covered by three-inches of ice, but not the pocket water. It’s always open and flowing, with a little ice around the rocks and boulders.

Nymphing is usually going to be the most productive method this time of year. The only exception would be if a hatch is occurring. During winter, this would be blue winged olives (BWOs) or midges.

Pocket Water Fly Fishing Gear

If you ask ten fly anglers to describe the ideal streamer rod, for example, you will get ten different answers. You can take that to the bank.

All I can do is convey to you my impressions and preferences, and let you digest the information and make your own decision.

The best all-around fly rod is a 9-foot 5-weight, and that’s what I use the vast majority of the time. But, not in pocket water.

Initially I did use a 9-foot 5-weight fly rod in pocket water too, but the close-range casts and annoying hang-ups in trees meant I needed to find a better solution. I thoroughly enjoyed the experience, but my equipment wasn’t ideal for the job, that I knew.

Shortly thereafter, something I read convinced me that I might like a 7.5-foot 3-weight instead.

So, I took a leap of faith and ordered one.

Everything changed overnight.

The close-range casts were so much easier, my accuracy increased, and I wasn’t getting hung-up on my backcast any longer. A chorus of angels could be heard singing in the distance.

Pocket water trout are, generally speaking, not big fish. A 3-weight is plenty to bring them to the net quickly 99.5% of the time.

I prefer to cast dry flies in pocket water, but if you’re going to be focusing on dapping and high sticking, you may want a longer rod closer to 10-feet. A longer rod will be an advantage in these non-casting scenarios because you’ll have a greater reach and more control.

A fly reel is an afterthought in pocket water. You’ll rarely, if ever, put a fish on your reel. Just strip them in quickly. If you’re having to reel in a 9-inch trout, you’re doing something wrong.

Just choose a reasonable reel that matches your rod’s weight and you’re good to go.

Use a weight-forward (or double-tapered) floating fly line in pocket water–a sinking or sink-tip line would get hung up constantly.

I use a 7.5-foot 5X or 6X leader. I then tie-on whatever length of tippet I prefer.

Summary

Fly fishing in pocket water is a good workout, you’ll find that there’s very little competition from other anglers, and the fish are usually aggressive feeders.

Not to mention, you’re usually surrounded by nature. I see frogs, mink, birds, snakes, and once even a black bear. I always enjoy seeing all the stonefly exoskeletons stuck to the surrounding rocks and boulders.

If you fly fish but haven’t explored pocket water, hopefully I’ve provided you with the knowledge and confidence you need to be successful your next time on the river.

Oh, and don’t forget metal cleats for your wading boots–pocket water rocks are slippery [major understatement].

About the Author

My name's Sam and I'm a fly fishing enthusiast just like you. I get out onto the water 80+ times each year, whether it's blazing hot or snow is falling. I enjoy chasing everything from brown trout to snook, and exploring new waters is something I savor. My goal is to discover something new each time I hit the water. Along those lines, I record everything I learn in my fly fishing journal so I can share it with you.

Follow me on Instagram , YouTube, and Facebook to see pictures and videos of my catches and other fishing adventures!