FLY FISHING FOR BROWN TROUT | FLIES AND TECHNIQUES

Dec. 2nd, 2021

There’s no denying that fly fishing for brown trout is considered an elite pursuit. As a species, these fish are elusive, selective, and reach monster sizes. In order to catch these trout on a fly, you’ll need knowledge, tactics, and strategies.

Often simply referred to as a “Brown” in fly fishing circles, the wild brown trout is a highly esteemed fish that’s considered more challenging to catch than many other species.

I’ve hooked into many hundreds of brown trout on the fly, in various states, during spring, summer, fall, and winter. In this article I’ll explain to you exactly how to catch these incredible trout with a fly rod in your hand.

It doesn’t matter whether you’ll be chasing brown trout in a river, stream, or lake—the following techniques and tactics will still apply.

Here’s a nice 22-inch brown trout I caught recently on a size 22 dry fly.

Table of Contents

Introduction

Brown Trout Size

What Brown Trout Eat

Where to Find Brown Trout

Brown Trout Fly Fishing Rods

Brown Trout Fly Line

How to Catch Brown Trout on a Fly

Dry Flies for Brown Trout

Nymphs for Brown Trout

Mousing for Brown Trout

The Best Flies for Brown Trout

When to Fly Fish for for Brown Trout

What is a Tiger Trout?

Summary

Introduction to Brown Trout

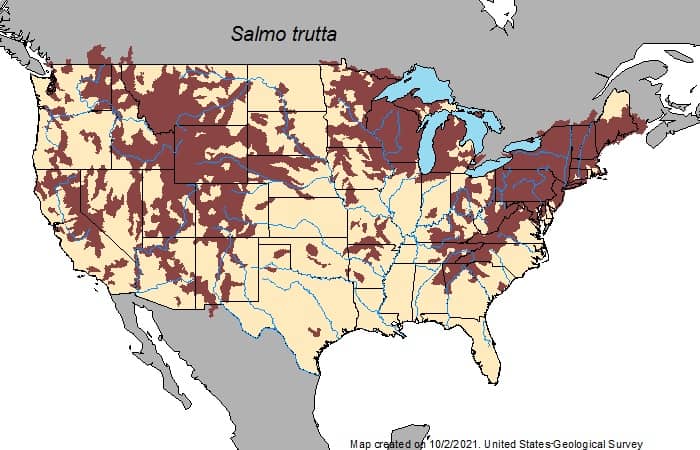

The brown trout’s scientific name is Salmo trutta. In Latin, Salmo means “Salmon” (they’re in the Salmon family), and trutta literally means “trout.”

These large fish are of European descent; they were never native to North America. It wasn’t until 1883 when a shipment of eggs from Germany arrived in America. The shipment contained a total of 80,000 eggs, which were cultured at fisheries out East. Since then, brown trout populations have spread across most of the nation.

Nowadays, brown trout populate a territory that spans across the entire U.S., as seen below in this USGS map of their range.

They are such an adaptable fish that, due to stocking in past decades, you can actually catch them in the Himilayas, and even the mountains of Kenya. With the notable exception of Antarctica, brown trout can now be found on every continent.

Along with being adaptable, brown trout are also aggressive predators. Brook trout are often forced-out by the bigger and stronger browns if both are occupying the same river or stream. Not only that, browns will literally eat the brook trout.

Browns can also withstand considerably warmer water than brook or rainbow trout, which also becomes a territorial advantage for them.

It’s this wild and powerful disposition that helps give brown trout their allure to fly fisherman. Catching one on a fly is a badge of honor, and it never gets old.

Brown trout size

The average size of a brown trout in most rivers or streams I’ve fly fished is between 9-16 inches. But, you’ll catch plenty that are smaller than that, and plenty that are bigger.

If you catch one that’s 20-inches or longer, congratulations, that’s an impressive size and something to be proud of. In other words, browns that are 20+ inches are massive. Browns over 22-inches are near-trophies. Anything over 24-inches is a trophy. These are my personal standards, others may disagree.

Quick tip: I never lay fish out and measure them with exactness—it keeps the fish out of water too long. Instead, I use the distance between the tip of my middle finger, and the bend of my elbow. I know the length is 17”, and it serves me well as a measurement. I can also use my net while it’s in the water, since it has measurements engraved into it.

The largest (IGFA all tackle world record) brown trout weighed 44.3 pounds and was caught in New Zealand. It looked like a monster.

The longest brown trout caught on a hook was in Wisconsin and was 38-inches long. Think about that—longer than a yardstick.

I see a number of monster browns while I’m wading in rivers that I frequent, especially when flows (cfs) are down and the trout are more visible. Very recently, in fact, the largest brown trout I’ve ever seen (in person) jumped several feet out of the water about ten feet in front of me. It was almost like the fish was teasing me. I’d estimate it was around 26 inches. So, I can’t even imagine what a 38-inch brown must look like cruising the water.

Below is a picture of a brown trout I caught while fly fishing recently–it’s a beauty, and only around 16-inches long. But, it’s a nice fish.

The average lifespan of a brown trout falls within the 4-6 year range, while the big ones are very feasibly 10 or more years in age.

Here are some state-by-state brown trout records, almost none of which were caught on a fly:

|

Arizona |

22 pounds 14.5 ounces |

|

Arkansas |

40 pounds 4 ounces |

|

California |

26 pounds 8 ounces |

|

Colorado |

30 pounds 8 ounces |

|

Connecticut |

16 pounds 14 ounces |

|

Georgia |

18 pounds 6 ounces |

|

Idaho |

27 pounds 5 ounces |

|

Illinois |

36 pounds 11.5 ounces |

|

Indiana |

29 pounds 03 ounces |

|

Iowa |

15 pounds 6 ounces |

|

Kansas |

4 pounds 9 ounces |

|

Kentucky |

21 pounds 0 ounces |

|

Maine |

23 pounds 5 ounces |

|

Maryland |

18 pounds 3 ounces |

|

Massachusetts |

19 pounds 10 ounces |

|

Michigan |

41 pounds 7.2 ounces |

|

Minnesota |

16 pounds 12 ounces |

|

Missouri |

26 pounds 13 ounces |

|

Montana |

29 pounds 0 ounces |

|

Nebraska |

20 pounds 1 ounces |

|

Nevada |

27 pounds 5 ounces |

|

New Hampshire |

16 pounds 6 ounces |

|

New Jersey |

21 pounds 6 ounces |

|

New Mexico |

20 pounds 4 ounces |

|

New York |

33 pounds 2 ounces |

|

North Carolina |

24 pounds 10 ounces |

|

North Dakota |

31 pounds 11 ounces |

|

Ohio |

14 pounds 10.8 ounces |

|

Oklahoma |

17 pounds 4 ounces |

|

Oregon |

28 pounds 5 ounces |

|

Pennsylvania |

19 pounds 10 ounces |

|

Rhode Island |

7 pounds 9 ounces |

|

South Carolina |

17 pounds 9.5 ounces |

|

South Dakota |

24 pounds 8 ounces |

|

Tennessee |

28 pounds 12 ounces |

|

Texas |

7 pounds 1.92 ounces |

|

Utah |

33 pounds 10 ounces |

|

Vermont |

22 pounds 3 ounces |

|

Virginia |

14 pounds 12 ounces |

|

Washington |

22 pounds 0 ounces |

|

West Virginia |

16 pounds 0 ounces |

|

Wisconsin |

41 pounds 8 ounces |

|

Wyoming |

25 pounds 13 ounces |

What Brown Trout Eat

Young brown trout are very insectivorous, meaning their diet is primarily comprised of insects such as mayflies, caddisflies, and even tiny midges.

They eat the larval (sub-surface) and adult (winged) forms of these insects.

They’re also very opportunistic feeders, more than willing to consume a grasshopper, ant, or spider that happens to fall into the water. Similarly, smaller fish are also prey items, including various minnows, baby trout, dace, and small sculpins.

Here’s a fat brown trout I landed on a small streamer pattern. The reason I took a picture of this fish is because it had significance–it was the 50th brown trout I caught that day.

Once brown trout reach a size of around 12-14 inches, they begin to have a more piscivorous appetite. In other words, they tend to target fish, and this is why streamers generally work well for more mature brown trout (more on this later). While they may prefer fish, big brown trout very willingly eat other large prey items such as rodents and frogs.

I’m a member a fly fishing club in one of the western states, and the owner of the club told me a story that opened my eyes to how truly predatory brown trout can be.

He told me that a fellow member had recently landed a good-sized brown trout one evening. The fish was unfortunately bleeding profusely, so rather than throw the fish back into the water where it would slowly perish, the angler decided he’d check the stomach contents of the trout.

Inside the fish’s stomach he found six small mice.

“Mousing” is a term dedicated to the act of casting flies that resemble small mice into the water at dusk. The purpose is to lure big brown trout out from the shadows—giant fish that begin prowling for meals once the sun sets.

It’s often said that night fishing for brown trout is when mousing is effective, but the truth is, mousing can be effective any time of day.

Big brown trout don’t necessarily feed every day—they can consume larger prey items and digest for days.

I can’t attest to the validity of this claim, but a photograph provided by a man named Sean Colenso shows a picture taken by a survey diver in New Zealand showing a brown trout that perished attempting to eat a small rabbit, pictured below.

As you can see, brown trout are voracious predators. This is one reason they’re so fun to chase with a fly rod.

Where to find brown trout

Brown trout are most often found in rivers and streams (flowing water), but some do habituate to lakes and other still water areas. They’re often found in bodies of water that also contain rainbow trout.

In fact, browns are found in 46 of the 50 U.S. states (and most of lower Canada) where they can be caught in all types of water from cold alpine streams to massive warm water rivers.

Right now you’re thinking, “Ok, so you’re saying they can be caught virtually anywhere. Where do I start?”

Firstly, I’d recommend referencing the USGS range maps (see above), and find rivers where browns are known to inhabit.

Secondly, you might consider hitting your local fly shop (and your local fly fishing forums) to get more information.

Brown trout will be hanging out in the usual places within river systems. In my experience, browns are generally in flowing water 8-36 inches in depth. However, I’ve caught them in 10-feet of crystal clear flowing water with dry flies, so you need to keep an open mind.

One of my favorite places to cast for brown trout is just beyond the end of a riffle. Trout tend to congregate below (and in) riffles, or where a pocket water feeds into a run or pool, because these river features funnel insects and other prey items directly into their feeding path. The water is also highly oxygenated.

In fact, here’s a remarkably beautiful brown trout (look at those colors!) I caught in one of those spots, just below where a riffle fed into a pool.

Undercut banks are well known gold mines for big brown trout. These are areas where the water’s current has carved-out a section of land below the grassy surface, providing secure overhead cover, and a spot where terrestrial creatures enter the water, whether intentionally or inadvertently. As a result, this is where many experienced fish hide-out and wait to ambush prey.

Monster brown trout—the ones you read about—can be found anywhere within a river system. They can’t be pigeonholed.

They can be found hanging around sunken trees and other structures, but that’s definitely not a rule. They often hold in pools and runs where they’re really good at blending in and avoiding detection while they digest their big meals (think mice). These trout usually feed at dusk or at night, and can travel vast distances in one evening.

Finding Trophy Brown Trout

One day in September I was walking along a river and noticed a trophy brown trout simply holding near the shoreline in two feet of water. Always be on the lookout, because you never know where you’ll find the big ones.

There was a study published in 1988 by David F. Clapp for the Michigan DNR which detailed the migration patterns of trophy brown trout (Salmo trutta). The experiment was done with radio transmitters implanted into the large trout. There were some interesting findings.

The shortest range of travel was 370 meters, and the longest was over 20 miles. The average range of travel was 3.04 miles during summer, and 7.39 miles during winter.

These trophy brown trout used “home” locations often (they had from one to four “homes”), from 86% to 97% of their time during summer, and 25% to 40% during winter. The average distance between their home sites was 386 meters.

In holding areas, the trout prefered bottom water velocity of less than 10cm (3.9 inches) per second. Their home sites were usually near logs, overhands, and vegetation.

The trophy browns in the study preferred holding depths of between 31cm (12.2 inches) and 60cm (23.6 inches), and also greater than 75cm (29.5 inches).

In June, their activity peaks were seen at 1am, 5am, 2:30pm, and 10pm. In July, the peaks were around midnight, and at 5am. In August, there were no observed peaks in activity, although a nadir (low point) was seen at 11am.

There was no discernable preference for traveling downstream or upstream.

There was another study done in 1975 by J.M. Elliott that found brown trout had the largest appetite in water temperatures between 56F and 65F, but that it was greatly reduced at temperatures above 65F.

It was discovered that their appetites only slowly declined at temperatures of 56F down to 44F. Their feeding was determined to be erratic at water temperatures below 43F and above 66F.

Here’s a beast of a brown that I caught on a size 20 PMD dry fly in early August.

brown trout fly fishing rods

There are two sides to this coin.

The ideal all-around brown trout fly rod is a 9-foot, 5 or 6-weight. Personally, I use a 9-foot 5-weight rod if I’m casting dry flies or nymphing. Whether it’s medium or fast action is determined by your personal casting preference.

The only tactical caveat here is that if you’re dedicated to chasing monster brown trout, and you want to toss big articulated streamers, you’ll want to consider a 7 or 8-weight rod. This is because a heavier rod will make casting heavy streamers much more manageable, especially in the wind.

My favorite streamer rod is a fast action 9-foot, 7-weight.

With that said, I often cast small streamers—sometimes all day—with my 5-weight. It’s your decision—there’s no right or wrong answer, just opinions and preferences.

Some fly fishers use lighter-weight rods in order to inject some added excitement and challenge into the process of landing a fish. But this is short-sighted and I don’t recommend it because if you can’t land a fish relatively quickly, you’re unnecessarily exhausting it. This can lead to lactic acid build-up and eventual death for the trout.

Any fly reel within reason will do just fine. I’ve never caught a brown trout that I couldn’t strip-in. In other words, it’s very rare to have to put a brown “onto the reel.” That might surprise you, but read on.

Most of the brown trout you hook into won’t take out line, otherwise known as taking out drag. A big one can, but even fish up to 20-inches often won’t, unless they get downstream of you (that’s another story).

I’ve had plenty of brown trout take out miniscule amounts of line during violent head-shakes, or when they initially grab my streamer then turn around quickly.

Rainbows are an entirely different story—I’ve had 18-inchers make my drag yelp while they peeled line off my reel, bolting to the other side of the river.

Speaking of gear, a great slingpack or backpack is an invaluable piece of equipment for any angler. If you’re curious, don’t miss my article on the best fly fishing slingpack I’ve ever used (and I’ve used quite a few).

brown trout fly line

Get yourself a weight-forward floating fly line.

I’ve mentioned in other articles that the first 35-feet of weight-forward line and double-taper line is identical, so if all you have is double-taper line, that’ll work too.

Match the weight of the line to your rod. So, if you have a 9-foot 5-weight rod, get 5-weight floating line.

Don’t overthink it, but do buy brand name fly line, such as Rio, Scientific Anglers, or Umpqua. I’ve used all three with no issues, but I tend to prefer Rio and Umpqua.

I generally recommend a 4X or 5X 9-foot knotless tapered leader with 3-feet of 4X or 5X tippet tied-on. Going down to 6X or smaller is asking for trouble with brown trout (their teeth are sharp), unless you’re using tiny dry flies (sizes 20-24).

If you’re casting streamers to brown trout, you don’t need a long leader. If you ask ten streamer fly fisherman what they’re preferred line setup is, you’ll get ten different answers. No question about it.

With that said, I use a 7.5-foot 1X leader, no tippet. Sometimes I snip the leader down to 5-6 feet. A thicker leader allows you turn-over the streamer more effectively when you cast (the line diameter is thicker and thus stronger), protects against abrasions, and of course stands up better against big, toothy browns.

Here’s a close-up photograph I took of the teeth inside the mouth of a sizeable brown trout I caught on a streamer.

How to catch brown trout on a fly

Brown trout are very willing to take your fly pattern. They’ll eat dry flies, wet flies, nymphs, and streamers. But there’s a time and place for each.

With that said, let’s get into some details.

In this section I’m going to explain techniques and tactics for catching brown trout with each type of fly (dry, wet, nymph, streamer). In the subsequent section, I’ll go into detail on the exact flies I’ve used to catch brown trout with great success.

As I explain strategies and make recommendations, always remember that you should always experiment on your own. Don’t take my word for it. You’ll absolutely discover new tactics that work on the rivers and streams you fish.

I’ll operate under the impression that you already know the fly fishing basics, such as making sure your flies don’t experience drag.

Also, don’t miss my in-depth article all about fly fishing for rainbow trout.

Dry Flies for Brown trout

Brown trout will very willingly rise to dry flies. In fact, casting dries is my favorite method of fly fishing for brown trout. The best time to tie-on a dry fly is during a hatch. You’ve heard it a million times, but I’ll say it again: match the hatch.

When you arrive at a river or stream, you’ll either see fish rising, or you won’t see fish rising. Pretty simple first step.

If you see trout rising, watch the water closely to see what they’re sipping (eating). You may see a hatch in progress but check the water’s surface anyway because multiple species may be hatching at the same time, and fish may be keying in on one of them. For example, blue winged olives (BWOs) and midges often times hatch simultaneously.

Don’t just squint and stare at the water out in the middle of the river. If possible, wade out and stare directly below where you’re standing (at your feet).

You’ll likely see small, winged insects drift by every few seconds. Some hatches are huge, and some are minimal, so the quantity of bugs on the water is never the same.

For example, if you see blue winged olives or duns (very common species of mayfly), try to determine what approximate size fly would be comparable to the insects you’re seeing. Size 18-22 is common, but sometimes the insects are larger, and sometimes smaller.

If you see trout rising but no hatch going on, it may be occurring sub-surface. Use a small net to sieve the water, and see what you find. This may mean you use a nymph or emerger pattern instead.

If the trout are rising but not taking your flies, and you’re sure you’re getting a dead drift (ie. no drag), then go smaller. Here’s a good rule: when in doubt, use smaller flies.

It might seem counterintuitive, but it often works. And there are some big browns that have been caught on size 22-24 dry flies. Big fish don’t always eat big meals.

A year or so ago, I was fishing in the midst of a blue winged olive (BWO) hatch. Trout were rising everywhere, but I wasn’t getting any takes. I’d been using a size 18 BWO, but as soon as I switched to a size 20, the fish started taking my flies. I’ll say it again: when in doubt, go smaller.

If you don’t see trout rising, don’t despair, you can try using dry flies anyway. I’ve done this many times, and it can be very successful. It’s called blind casting, or searcher casting. In other words, the trout don’t have to be rising for you to use dry flies effectively.

Here’s a brown that took one of my blue-winged olive flies, a size 18.

If you know what the hatches look like on your home waters, then you already know what size dry fly to try when there’s no hatch occurring, or at least a general size range.

If you’re new to the waters, I’d try a dry fly sized 18 or 20 to test things out.

Once you have a successful day on the water, don’t get over confident. Dry flies that worked last week may not work at all this week. That’s how river trout behave sometimes. In short, be adaptable.

A few weeks ago, I prospected a new river and hooked into 16 brown trout on a size 14 dry fly. They were good-sized fish, and it was a blast. Here’s one of the 16 browns I connected with–an 18-incher caught on a dry fly pattern in late summer.

The following week I went back with the same setup, and the trout treated the same fly like the plague. I tied-on a totally different looking dry fly (size 14), and they went nuts for it. Don’t ask me why, no one knows. But it happens.

Matching The Hatch

You’ll start to recognize the types of hatches on your home waters, but you don’t have to become an amateur entomologist to successfully fish with dry flies.

Some folks take great pride in being able to identify every species of mayfly. I read about a man who took two years off from fly fishing so he could study and become an expert on hatch insects. In his book Rivers of Sand, Josh Greenberg said that’s like taking two years off from dating so you can practice kissing. So true.

If you’re in the middle of a blue winged olive hatch and you tie-on a fly that somewhat resembles a blue winged olive, and you have the fly size dialed-in, the trout will likely accept your offering. There’s usually no need to overcomplicate matters or fret over exact fly coloration.

Here’s a real-world example of what I’m trying to convey.

I was fishing a river in the sierras one winter afternoon and there were trout rising to what looked to me like blue winged olives. They might’ve been another species of mayfly, I wasn’t exactly sure.

So I tied-on a size 18 blue-winged olive (BWO), but saw no reaction from the trout for 20-30 minutes.

I went smaller and tied-on a size 20 blue-winged olive and ended up hooking into several very nice rainbow and brown trout over the ensuing couple hours. But then things slowed and after 30+ minutes of no action, I switched to a size 20 yellow sally, and the trout started taking my fly again.

Here’s my point: blue-winged olive flies look nothing like yellow sally flies. Their design and coloration are nothing alike. And I’d never seen a yellow sally mayfly on that river. Yet the fish accepted both.

In the above example, I’m very confident I could’ve used a size 20 adams with equal success.

So, don’t agonize over fly selection. Experiment. Try different sizes and patterns.

Don’t get me wrong, sometimes one fly will work when others won’t. But that’s why you experiment. I’ve never spent much time learning the differences between this mayfly and that mayfly, or this caddisfly and that caddisfly. You’d be better served practicing your knots, practicing your casting, and getting out on the water.

You don’t need to become an entomologist to be successful. Just by getting out there you’ll learn enough about hatches to be dangerous.

Nymphing for brown trout

Nymphing for brown trout can be devastatingly effective, and when compared to using dry flies, it’s a higher probability method for hooking into a trophy-sized fish.

Whether you tie-on one or two nymphs under an indicator, or a nymph behind a dry fly (called a dry-dropper), this will generally be the most productive method when you’re chasing brown trout.

I’ve heard many fly fisherman parrot that trout feed 90% of the time below the surface, and just 10% on the surface, so if you’re not nymphing you’re missing out on a huge number of fish.

While I’m not sure where those percentages came from, nymphing is definitely effective. If you’re into action, nymphing is probably your thing.

Here’s a 22-inch brown trout I caught on a pheasant tail nymph in a riffle that was just 12-inches deep.

In my experience, brown trout aren’t picky when it comes to nymph patterns.

Here’s what I mean.

A few weeks ago I fished a river in the mountains for several hours using a dry dropper setup. A dry dropper is when you have a bulkier dry fly trailed by a nymph. The dry fly effectively acts as your indicator, but can obviously catch fish as well.

Specifically, I was using a pheasant tail nymph. After several hours, I’d landed over 20 brown trout, none under 12-inches, and the biggest around 18-inches. Most had taken the nymph.

Because of this, I decided to experiment. I removed the pheasant tail nymph and replaced it with a hare’s ear nymph of the same size. I wanted to know if the trout were selective.

The fishing didn’t slow down at all. The trout took the hare’s ear nymph with the same relish they took the pheasant tail nymph.

But admittedly, those two nymphs look somewhat similar—and nymphs usually travel through the water relatively quickly, which means trout don’t have much time to analyze the offering.

Along those lines, I removed the hare’s ear nymph and tied-on a copper john nymph in the same size.

The browns started taking the copper john nymph with the same gusto as my two prior offerings.

So, don’t agonize over which nymph to use. Always keep a few pheasant tail, hare’s ear, copper john, and prince nymphs in your fly box and you’re basically set for life. If I could only use one nymph pattern when angling for brown trout, I’d choose the pheasant tail.

It’s my honest opinion that you’ll never need any other nymph patterns, regardless of whether you’re chasing brown trout, rainbow trout, brook trout, or even carp.

Let’s get back to the nitty gritty.

Nymph Strategy

The distance between your indicator (or dry fly in a dry dropper rig) and your nymph should generally be 1.5 to 2 times the depth of the water. The current is the determining factor.

You want your nymph getting hung-up every few casts. This might be frustrating, but it tells you you’ve got your fly riding low, near the bottom. That’s where you want your nymph.

If you’re not getting hung-up occasionally, increase the distance between your indicator and your nymph, or add weight. Or both.

Fish your nymphs in areas with a nice current, within the range of 2-3 feet per second. Put another way, if you dropped a leaf onto the surface of the water, it should travel 2-3 feet in one second. That’s ideal water.

In contrast to the above picture, here’s a baby brown trout I caught on a soft hackle pheasant tail nymph while swinging flies.

Streamers for brown trout

Streamers are synonymous with chasing big brown trout. As the saying goes, “The tug is the drug.”

Remember when I mentioned as browns age, they become more piscivorous? That’s why streamers tend to be a good option if you’re focused on monster brown trout—they can be fished to resemble dace, sculpins, and baby trout, all favorite foods of big browns.

Find out what prey fish live in your river and buy some streamers that have a similar appearance.

Cast your streamer quartering upstream (45-degrees upstream), or directly across stream (90-degrees), as close to the bank as possible. Let it sink for a moment. Give it a couple short strips. As the current carries the streamer past your position, begin stripping faster until the streamer is directly below you.

At this point some fly fishers continue stripping the streamer straight back upstream to where they’re standing, and others begin preparing for another cast. Personally, I continue stripping the streamer about halfway back to my position before casting again.

Vary your stripping rate. Brown trout often like a slower strip, but sometimes they hit a faster strip more willingly. Again, experiment.

You can use floating line, sink-tip line, or full sinking line when casting streamers. All will work, with varying degrees of effectiveness depending upon the water you’re fishing. Experiment.

I’d recommend having a dedicated streamer rod if you’re going to seriously pursue browns using this method.

Here’s a nice little brown I took on a streamer in October. I remember this fish well because I watched it trail behind my streamer as I stripped it in, just before the fish accelerated and slammed my fly. It was like watching a shark close-in on its prey. Never pause your stripping while a trout is trailing your streamer. If you do, the fish will lose interest.

Usually, the best days for throwing streamers for brown trout are dark, rainy, and/or cloudy days. But don’t ever listen to someone who says you can’t catch brown trout on sunny days. You can. I have many, many times. Some of my most productive days have been in the bright unrelenting sun using streamers, nymphs, and even dry flies.

There’s a saying: dark day, dark fly; bright day, bright fly. It means during a dark day, use a dark-colored fly (black, etc). When it’s bright out, use a light-colored fly (white, etc). This is decent advice for streamer fishing, but I wouldn’t call it a rule. Try it. If it doesn’t work, break the rule and do the opposite.

When the water is just a little tainted the brown trout seem more apt to take a fly. This can happen during or after a rain when the water rises, and it can happen when the water level falls too (this happens on tailwaters with regularly scheduled flow changes).

The consensus is that less clear water makes the fish feel more secure. Also, rising water levels can flush more prey items into the river.

Here’s a short video I took while releasing a 19-inch brown trout after it had taken a streamer I was using with the continuous strip-pause-strip method.

Mousing for brown trout

“Mousing” for brown trout involves casting a floating mouse pattern fly and stripping it back to your position. It’s a low probability fly, but the quality makes up for the lack of quantity.

These rodent-imitating flies are best fished in low-light conditions, but ideally at night when monster brown trout are patrolling the shoreline. It’s a quintessential night fly.

I heard an accomplished fly fisherman say that while mousing is considered a nighttime activity, he’s caught plenty of trout in the middle of the day just casting a mouse fly across the current and stripping it in.

If you’re interested in some detail, I wrote an in-depth article on mousing for brown trout.

The best flies for big brown trout

Pheasant tail nymph

This is an iconic subsurface fly pattern that every fisherman or woman should have in their fly box, regardless of whether you’re chasing brown trout or not. Fish it with an indicator, or under a hopper, size 16-22.

You can get this fly in a beadhead (if you need to get it down), non-beadhead (if you’re already using weight), and flashback (reflective material) styles—and they all work.

If you don’t have this nymph in your box, you’re not taking fly fishing seriously.

Honorable mention: Hare’s Ear nymph, Prince nymph, Copper john nymph

Blue Winged Olive (BWO)

This is another must-have dry fly pattern, whether you’re chasing brown trout or not. In my experience, it’s most productive in sizes 18-22, when browns are sipping small mayflies on the surface. Once in a while I tie-on a size 24, but they’re tough to track on the water at dusk and dawn, even with my excellent vision.

Not only is this fly pattern an imitation of a very commonly seen hatch (BWOs), but in sizes 22-26 they are also excellent midge imitations. Browns of all sizes, even big ones up to 20-inches, will often rise to take tiny surface flies (especially during winter). Speaking of that, consider reading my popular article on tips for winter fly fishing.

I like the comparadun version the best, but the standard BWO (or parachute pattern) works well for me too.

Honorable mention: Adams (or Parachute Adams), PMD (Pale Morning Dun)

Elk Hair Caddis

This dry fly isn’t just productive when caddisflies are hatching—far from it. It’s a meaty fly that gets the attention of brown trout, and it doesn’t drown easily (Elk hair is hollow). It can imitate so many things—caddis, caterpillars, spiders, moths, grasshoppers, etc. It’s like a cross between a standard dry fly and a hopper.

I recommend sizes 12-16. I occasionally trim the fly so it sits a little closer to the surface. I’ve caught a lot of small-to-medium sized brown trout on this fly.

Honorable mention: X Caddis

Woolly Bugger

There’s a reason this is perhaps the most popular streamer fly ever created. I’ve heard a few accomplished fly fisherman say if they could only use one fly for the rest of their lives, it’d be this one.

The reason is, it mimics so many different prey items, including sculpin, leeches, crayfish/crawdads, and more. It’s also versatile—you can bounce it off the bottom, or fish is close to the surface.

There’s a beadhead, and non-beadhead, version depending upon how you want to fish the fly. Black is the color I’ve had the most success with catching brown trout. I’d recommend sizes 4-10.

The retrieval I’ve had the most success with is short, quick, successive strips.

Drunk and Disorderly

Also referred to as the Double D, this articulated streamer pattern is a real producer—it brings big fish to the net. It’s easy to cast (with a 6-7 weight fly rod), which is unusual for bigger streamers, and it has great motion in the water.

You can retrieve it any number of ways (experiment), but the creator of the fly (Tommy Lynch) says the best tactic is sharp, short strips with no rhythm.

It’s an excellent streamer fly if you’re going for monster brown trout.

Honorable mention: Barr’s Meat Whistle

Green Drake

The green drake hatch, which occurs during the summertime, is a favorite of fly fisherman. They’re big flies that illicit big strikes. The hatches generally begin in the late afternoon and evening and can continue until dusk.

Don’t be afraid of giving the fly a little action—it can trigger a strike.

The first brown trout I ever caught—a 16-incher—inhaled a size 10 green drake emerger pattern in Wyoming. But, don’t use this fly if the drakes aren’t out.

Chernobyl Ant

Originally tied to resemble a cricket, this versatile terrestrial hopper pattern has earned its reputation as a veritable trout magnet. It can imitate protein-packed crickets, grasshoppers, spiders, caterpillars, and other invertebrates.

I’ve used this pattern (size 8-12) to hammer browns and rainbows in the summer, especially when the trout aren’t rising. One technique I use is to give the fly a twitch as soon as it hits the water.

This foam hopper fly is nearly impossible to drown, which is a nice bonus.

Honorable mention: PMX, Fat Albert

Master Splinter

Named after the TMNT sensei, this is my favorite mousing fly for big brown trout at night. Avoid the cute mouse patterns that look like they belong in a toy bin. It’s all about profile, especially in the dark, and this fly has earned its keep.

It’s simple to tie, and deadly effective. When I first started stripping this fly in the evenings on my home river, even the smaller brown trout would try to take it down.

Which reminds me, this pattern floats for ages. It doesn’t get waterlogged, which is convenient when it’s dark out.

If you’re going to night fish for brown trout, this is your fly.

When to fly fish for brown trout

You can catch brown trout during any season, using any method. Don’t let anyone tell you differently. Things get trickier during winter, but it’s still a worthwhile venture.

Catching brown trout in the Fall

Fall is an exciting time to chase big brown trout because they’re preparing to spawn. Browns will usually begin laying eggs in November, but in the 4-6 weeks leading up to this time, they’re out cruising and eating in areas they otherwise wouldn’t be found, such as shallow riffles and pocket water.

Here’s a monster brown trout I caught in September, just ahead of their spawning season.

Brown trout get much more aggressive during the fall, and they’re less discriminating when it comes to eating. The most effective flies during this season are hoppers (and other terrestrial patterns), nymphs, and streamers. In other words, they’re in the mood to take your fly.

Brown trout spawning season

Brown trout lay eggs in areas of loose gravel, called “redds.” If you’re wading a river any time from late October and through December, please watch out for them. If you step in a redd, you’ll obliterate countless eggs.

Here’s a picture of a brown trout redd. Specifically, the light-colored area. Do you see how the surrounding river bottom is dark and covered with algae? The light-colored area is where the trout kicked-up the gravel and sand and laid eggs.

Be conservation-minded and realize that it’s considered extremely unethical to cast to a spawning brown trout—it sabotages the future of our fisheries. Don’t be a richard.

Here’s a brown that I landed while swinging flies during the fall. The fly in the foreground is a purple leech pattern and a stout rainbow trout hit it a few minutes after I landed this brown trout.

Catching brown trout during Winter

Winter is the slowest time of year due to the colder air and water temperatures. There are fewer hatches, and the fish just don’t need as many calories when the water is cold–they just aren’t as active. The cold water means fish usually don’t want to chase their meals, they’d prefer to eat something that drifts right to their nose.

The good news is, brown trout continue to feed all winter. They don’t have the luxury of not eating. This goes for all trout species.

Another nice thing about winter is that big brown trout are more willing to accept smaller meals, such as tiny BWOs on the surface.

If the water temperature drops below 35F, you might be better off tying some flies in the warmth of your home and waiting for warmer days. That’s not to say there aren’t winter hatches, though. Blue-winged olives and midges hatch throughout winter across much of the country.

Catching brown trout in the Spring

Springtime can also be a really productive time to go fly fishing for brown trout. The fish are putting weight back on after the arduous spawning season, and they’re on the hunt for calories. But, depending on where you live, winter runoff can cloud the water and increase currents, making some rivers unfishable until early summer. Tailwater rivers generally clear a little quicker than freestone rivers.

Again, streamers and nymphs are going to be your go-to flies for big browns during spring, but dry flies can also work well during hatches. When fish are rising, it’s tough to ignore the call of dry flies.

Catching brown trout in the Summer

Summer is hopper season. Tie-on something big and hit the water. Terrestrial hopper patterns that work well include grasshoppers, crickets, beetles, and ants. Speaking of ants, don’t forget to read my article on how to fly fish with ant patterns.

This past August I visited a river I’d never been to before. Based on research I’d done, I knew the water held trout.

After arriving at the river, I saw some sporadic rising trout. But, it wasn’t possible to get a fly to them because it was too deep to wade, and the shoreline was inundated with trees.

I finally found an area with very wadable water about a mile upstream. I tied-on a hopper and began wading. There were a few rhythmic rises along the opposite shore, so I carefully maneuvered towards the fish.

On my fourth cast, a trout rose and took my hopper. I knew immediately that it was a big fish.

Fortunately, the water was only a couple feet deep, and there weren’t any major obstacles like downed trees and sharp rocks.

I stripped the fish in, and it ended up being on of the largest brown trout I’d ever landed. Many more browns found my hopper irresistible that day. It was an epic summertime outing.

In summary, summer and fall are going to be your go-to seasons for brown trout fly fishing.

What is a tiger trout

While brown trout can withstand warmer water than brook trout, there are situations where they coexist.

If male brown trout populations are sporadic, female brown trout can spawn with male brook trout, creating a hybrid called a tiger trout.

However, researchers don’t believe male browns spawn with female brook trout.

Summary

Fly fishing for brown trout is an undeniably captivating pastime that’ll keep you engaged and experimenting year after year. The more time you spend on the water, the better you’ll get at bringing them to your net.

These much-heralded trout are rewarding quarry, and I encourage you to treat them as such. Strip them in quickly, and get them back into the water quickly. If you need to take a picture, keep the fish in the water with your net until you’re ready to snap the photo.

Browns live in almost every state, and there’s a good chance they’re within a reasonable distance of where you are right now. One of the best tools for planning fishing excursions is Google Maps. I’ve found some of my favorite spots using this method.

Now get out there.

About the Author

My name's Sam and I'm a fly fishing enthusiast just like you. I get out onto the water 80+ times each year, whether it's blazing hot or snow is falling. I enjoy chasing everything from brown trout to snook, and exploring new waters is something I savor. My goal is to discover something new each time I hit the water. Along those lines, I record everything I learn in my fly fishing journal so I can share it with you.

Follow me on Instagram , YouTube, and Facebook to see pictures and videos of my catches and other fishing adventures!